The City Beautiful movement – urban design and moral well-being

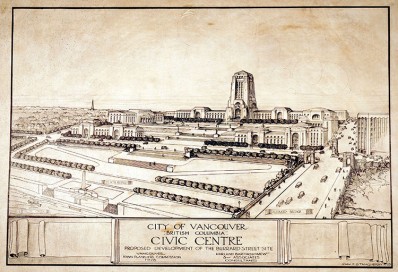

A proposed civic centre for Vancouver (part of the Bartholomew Plan, 1928).

The possibility that cities affect human behaviour is an enticing one, and the origins of this notion go back several millennia to the time of Plato. The basic idea of this relationship – between built form and ways of being – remains popular today, and takes shape in a number of forms. Think, for example, of some of the assumptions present in broken windows theory, or the idea of healthy built environment, two of many and divergent tangents on the theme of cities behavioral engineering.

Indeed, the idea that city-building can affect (or change) behavior has taken a number of forms – both in theory and in practice – over the course of history. Look at the history of urban design and you will see an intriguing cycle of idealism, controversy, critique and reform – often mirroring larger social, political or cultural shifts taking place.

In North America, one of the most enticing debates started in the late 19th century with the introduction of the City Beautiful movement, which emerged out of architect Daniel Burnham’s design for the grounds of the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Daniel Burnham’s Court of Honor and Grand Basin – from the 1893 World Columbian Exposition

In the years leading up to this milestone event, urban planning and city design were generally seen to serve strongly aesthetic and/or functional needs (defense, health, transportation, religious beliefs). The City Beautiful Movement (re) introduced the more nuanced idea that urban beautification actively improves the moral and social character of the citizen. In so doing, it elevated the act of city building, making it a mechanism for social control, which “would increase the quality of life and help to remove social ills.”

The movement was borne as a byproduct of French Beaux Arts neoclassical architecture. As opposed to just the architectural design of building structures, the Beaux Arts school also paid attention to urban landscaping emphasizing focal points such as grand plazas, wide avenues with terminating landmarks, symmetrical design, and huge monumental structures.

However, where these Beaux Arts principles were advanced from an aesthetic standpoint; the City Beautiful Movement went further by linking such designs to the idea of an improved citizenry, treating the planning elements as potential drivers social control and behavioural influence.

Under City Beautiful, the wide boulevards, elegant parks, recreational waterways and riverbanks, spacious public plazas adorned with grand monuments, were seen to portray the ideal utopian city – which in turn acted as an emblem of an idealized society filled with ideal citizens.

Particularly with respect to the grand structural designs and focal points, the easy-to-interpret City Beautiful designs that were showcased at the Exposition symbolized political superiority and control. In these models, citizens were seen to value, respect, and keep their surroundings beautiful and tidy, and thereby become more urbane and socially refined. Physically, the City Beautiful Movement also aimed to respond to concerns that rapidly growing cities were becoming overcrowded, blighted, immoral places.

Following the success of the Exposition, a number of North American cities adopted elements of the City Beautiful movement as a basis for urban planning and design. Chicago, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Cleveland and Detroit, were among a number that integrated Burnham’s ideas into their urban plans. In Canada, Ottawa and Regina were among cities that were influenced by the ideas. In Vancouver, the 1928 (and later expanded) Bartholomew Plan was shaped by the movement as well, though this was perhaps manifested (and built out) to a less obvious extent than in the other cities mentioned.

Many of the places mentioned have strikingly common similarities with respect to fanned-out road layouts, wide avenues, and focal centers that are often the locations of civic buildings in the city.

The McMillan Plan for Washington D.C. – inspired by the City Beautiful movement.

City Beautiful achieved considerable momentum through the early 20th century – perhaps, as been suggested by some critics – because of the perceived need for social reform in response to the increasingly overcrowded conditions found in American urban centres. But did the focus on virtue and behavior actually work? Did it get to the heart of the challenges faced by cities? Jane Jacobs, for one, charged that the movement was too focused on the role of design as a mechanism of change. She critiqued the City Beautiful movement for not going far enough to understand the social dimensions and complexity of a city.

To be fair, City Beautiful was an attempt to respond to these complexities – but it was also overwhelmed by them at the same time. Concurrent with the growth of the movement, was an ever increasing period of urbanization, with continued migration shifting people from rural areas to larger urban centers. The manufacturing sector was booming, providing the lure of steady employment. Yet in core areas of city after city, the response to these demographic changes was manifested in poor quality housing, lower wages and working condition and polluted cities due to the predominantly coal-fired industry. These social and economic hardships sparked an atmosphere of social upheaval, labor strikes, violence, squalid habitations, and disease-infested growing cities.

Within this context, the City Beautiful movement seemed to offer a solution. It emerged at a time when there were repeated calls for reform in city design in the United States… and a resurgence of interest in city building as a means to enable citizen improvement.

Ironically, the actual implementation of City Beautiful ideas actually reinforced urban inequality – as older slums and their tenement structures were cleared, and poor residents displaced, to make way for the sweeping boulevards and rigorous geometries of the new plans.

Perhaps a more nuanced analysis is appropriate. Rather than a panacea, the City Beautiful movement was beneficial in some contexts. Positive contributions of the movement can be seen in cities such as Washington and Chicago, where aesthetic enhancements of the building stock and revised road layouts can still be seen today.

On the other hand, City Beautiful is emblematic of the power of strong utopian idea over the harder demographic realities of early 20th century urban form. It’s hard to be ‘civilizing’ when the realities of economic security and industrial capitalism are driving other agendas. Similarly, movement that is located in that exalted territory between pure design and moral well-being is perhaps a bit too much shadow and not enough solid ground.

- by Paolo Fresnoza, with files from Stewart Burgess. An earlier version of this article was published for the Philippine Online Chronicle in 2010